The 20th century 'war tubas' used to spot warplanes before radar

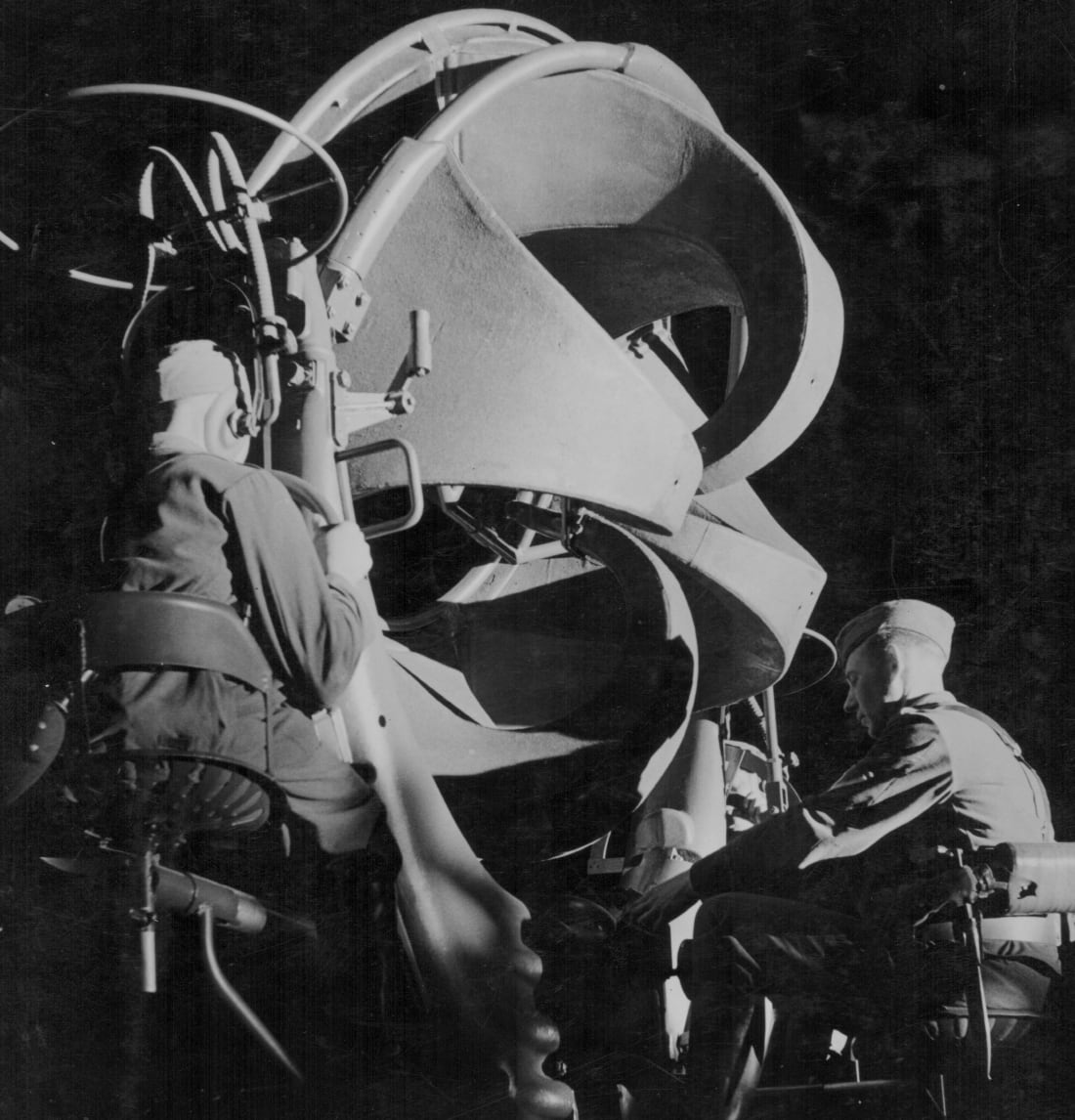

1 / 10 -Before the invention of radar during World War II, incoming enemy aircraft were spotted using "sound locators" that looked more like musical instruments than tools of war. This one was being used at Bolling Air Field, US, in 1921.

2 / 10 -A British military sound locator in use at an airfield in southern England, in 1930. On the left is a searchlight that was used in conjunction with the locator.

3 / 10 -A German anti-aircraft listening post during World War Two, circa 1939-1945.

4 / 10 -US military personnel operating airplane sound detectors as officers sit and monitor the readings, near San Francisco, California, circa 1944. The Golden Gate bridge is visible in the background.

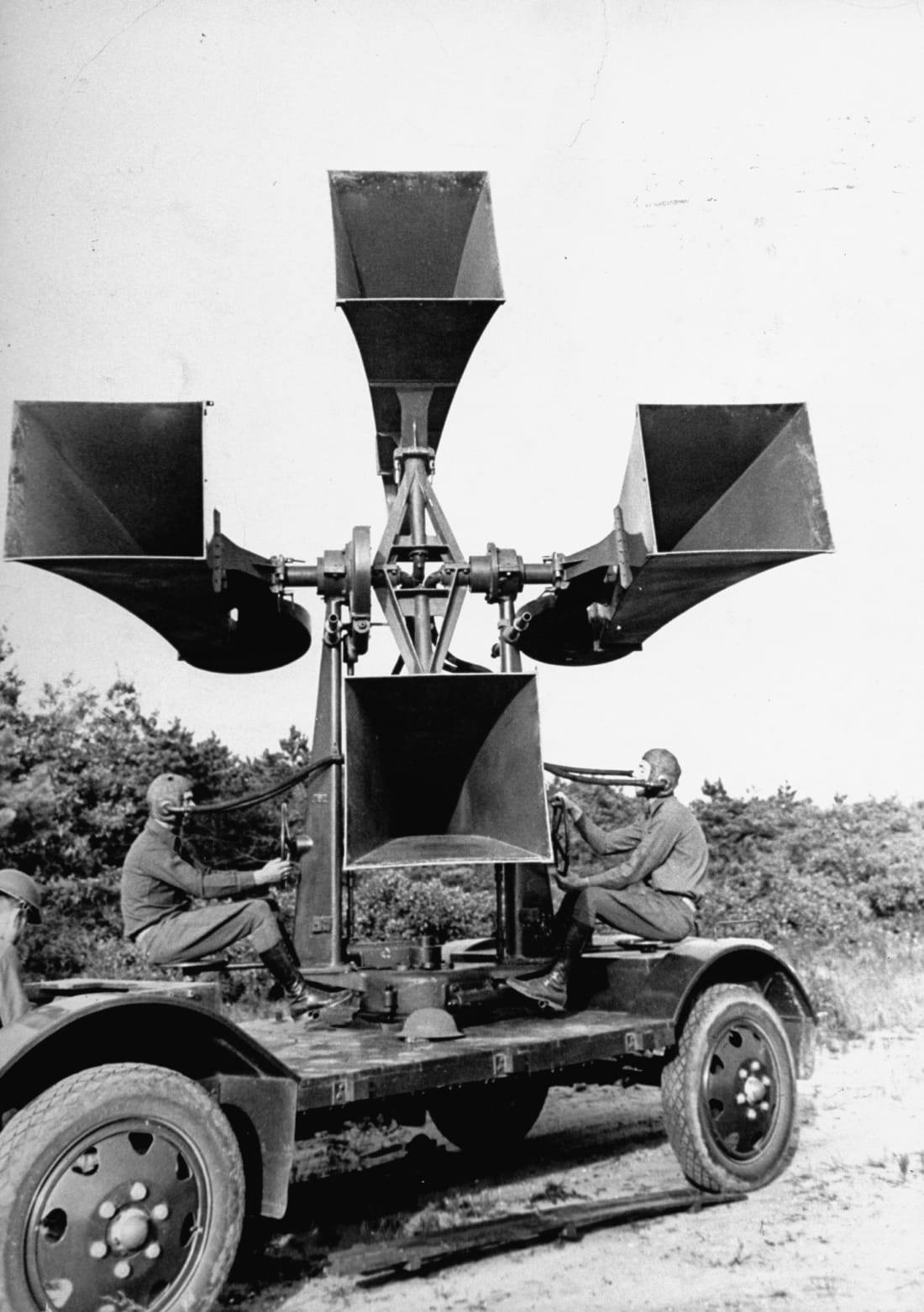

5 / 10 -Japanese soldiers demonstrate the use of a "war tuba."

6 / 10 -According to Phil Judkins, "sound locators worked reasonably well with rain and with cloud, but they tended to get a bit muffled with fog. Then again, in that period of time aircraft themselves tended not to fly in fog."

7 / 10 -After the introduction of radar, some of the trailers used to transport sound locators were repurposed for the new invention.

8 / 10 -An acoustic mirror near Hythe, Kent, south-east of England.

9 / 10 -Denge Sounds Mirrors on RSPB land near Lydd, Kent, south-east of England.

10 / 10 -A woman poses by a First World War "sound mirror" listening device at the Fan Bay Deep Shelter within the cliffs overlooking Dover, England. The National Trust rediscovered the tunnels after purchasing the land in 2012 and after a major restoration project, the tunnels are now open to the public.

Before the invention of radar during World War II, incoming enemy warplanes were detected by listening with the aid of "sound locators" that looked more like musical instruments than tools of war.

These radar forerunners, which earned the nicknames "war tubas" or "sound trumpets," were first used during World War I by France and Britain to spot German Zeppelin airships. The purely mechanical devices were, essentially, large horns connected to a stethoscope.

"It was a development of artillery sound ranging," explained Phil Judkins, a war historian and Visiting Fellow at the University of Leeds, during a phone interview.

"It had been noticed for quite some time that you could locate a gun if two or three or four different people listening to the gunshot each took a bearing." Combining the bearings, or the measurements of direction between two points, would give the location of the gun. That same process was then applied to listening for aircraft.

Limited range

A common configuration of the device had three horns arranged vertically plus an extra one to the side. The central one in the set of three and the lateral one were used to get the aircraft's bearing, while the remaining two were used to estimate its height. The operators would listen in through the stethoscope and tilt the horns until they got the loudest sound.

"That will then give you the direction, and with a little trigonometry it will give you the height of the aircraft," said Judkins.

Sound locators were used near the frontline in conjunction with anti-aircraft guns, but their range was limited to just a few miles. "The number of times any enemy aircraft was actually shot down using them is very small, or at least the number of recorded occasions that we know about. But the number of times any enemy aircraft was shot down using fighters and so on was pretty small as well," said Junkins.

Acoustic mirrors

To get better range, the British also experimented with a static type of sound locator, made of concrete and shaped like a dish or a curved wall, known as an "acoustic mirror." These were first trialled in the southern and eastern coast of England during World War I and then built in about a dozen locations throughout the 1920s and 1930s. They were up to 30 feet (9 meters) in diameter, but a wall-shaped one in Kent, 60 miles south-east of London, spanned 200 feet (61 meters) in length. Many other countries including Germany, Japan and the United States were also developing sound locators at this time.

Obsolete, but not forgotten

After 1930, microphones were used to pick up and amplify the noise, and later still, in 1939, the most advanced systems did away with sound completely and transformed the noise into a visual symbol on a cathode ray tube screen -- an innovation that came from the inventor of stereophonic sound, Alan Blumlein.

"They eventually achieved ranges of up to about 20 miles in good conditions. The thing that overtook them, quite obviously, was the increasing speed of aircraft, which in the late 1930s were traveling at between 190 to 240 miles an hour," said Judkins.